The Baseball

The village of Cooperstown, population 1,853, is nestled in upstate New York, not far from the Finger Lakes and some of the most beautiful rolling countryside you will see anywhere. The town itself is a simple grid, Main Street runs down the middle of town with Pioneer and Chestnut streets bounding the little business district which still has the feel of a place out of another era; a saner, simpler time where you might imagine a band playing John Phillips Souza music from a nearby gazebo, where folks rock on their porch chairs, fans in hand, sipping a cold lemonade. Sherry’s Famous Restaurant on Main looks like it might have opened 150 years ago; the same with the Short Stop Restaurant, The National Pastime, Mickey’s Place and Shoeless Joe’s Apparel and Souvenirs.

Main St. Cooperstown, New York (Photo - visitingnewengland.com)

The town gets its name from the same family that gave the world James Fenimore Cooper, author of the famous Leather Stocking novels, the most famous being Last of the Mohicans. In 1785, two years before the Constitution of the United States was written, James’ father William bought 10,000 acres of prime land at the southern end of Otsego Lake where he promptly built a mansion and created the village that became Cooperstown.

Farther down the road, about a mile north of town on state route 80, lies one of Cooperstown’s more famous sights, the Cardiff Giant, a petrified colossus, over 10 feet tall, discovered by workers digging a well in 1869; proof that giants once roamed the earth. Or that was the story, before it was discovered that an enterprising tobacconist named George Hull had made it all up. (He was an atheist and wanted to prove to a local Methodist Reverend that the Bible shouldn’t be taken literally.) Eventually the famous giant made his way from nearby Cardiff, New York to the Cooperstown’s Farmer’s Museum, where you can still ogle the fellow, lying prone on the ground.

That, and the Leather Stocking tales, would be all the fame that might ever have found its way to Cooperstown, except for one other thing.

On any given June afternoon, you’re likely to hear the sweet crack of a baseball bat sending a ball sailing into the outfield, or maybe screaming past third base, as if in pain. Those sounds would be coming from Doubleday Field, a perfect little baseball diamond, enclosed by bleachers and red brick — a closely cropped meadow of dreams where people come, like members of a religious pilgrimage, to watch and honor a strange game involving four bases, 18 players and an assortment of peculiar gear and equipment, the most central being a perfectly round orb, bound over with animal hide stitched together with 216 hand-sewn loops of bright red cotton thread. On the outside the ball is white, 9 inches in diameter, 5 ounces in weight. Inside, at the core is the “pill,” a small ball of cork surrounded first by two slender layers of hard rubber wound tightly around 121 yards of four-ply, blue-gray wool yarn. On top of that comes 45 more yards of three-ply, white wool yarn. Next, 53 yards of three-ply, blue-gray wool yarn bind the ball, until finally 150 yards of polyester-cotton blend white yarn finish the job. Then comes the two pieces of perfectly matched cowhide that together give the impression of a mysterious and infinitely entwined möbius.

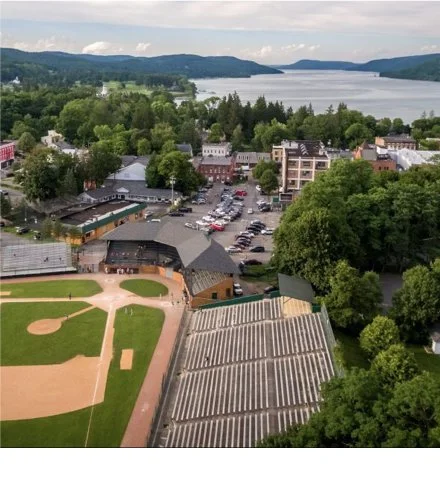

Doubleday Field (Photo - offmetro.com)

It is a very tight, history-laden little package.

Right next door to Doubleday Field, maybe a hundred yards away, sits the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Nearly 300,000 people a year visit the hall, and any one of them, if they are in the mood, can make their way to the second floor and find—right next to Honus Wagner’s bat and not far from the one of the 714 baseballs Babe Ruth hit over fields all over America—a very particular sphere that has been called the first of its kind: the Doubleday Baseball.

The Original Baseball? (Photo- Chip Walter)

It doesn’t look like much, up close. Its homemade seams are split, their ancient stitches frayed and its yarn stuffing lays exposed like the innards of a bad taxidermy job; all understandable since the thing is coming up on 200 years of age.

The Doubleday ball shows its age in other ways too. It looks different: it’s a dark, tobacco brown, and about two-thirds the size of a current baseball. Its hide cover, what remains intact, is gathered together by four separate strips, as if you had quartered an orange and stitched it back together. The infinity-mobius stitching hasn’t yet been invented.

Of all of the thousands of objects housed in the Baseball Hall of Fame, this was the first to find a home; the spherical equivalent of the tablets of the Ten Commandments once enshrined within the Ark of the Covenant; iron clad proof of the game’s invention. Stephen C. Clark, the founder of the Hall of Fame paid $5 for it, and it’s the only artifact in the museum that it actually owns.

The ball found its way into Clark’s hands from a trunk belonging to a mining engineer named Abner Graves. He happened to own it because he says he was in Cooperstown the day Abner Doubleday invented the game on June 12, 1839, all in one fell swoop.

The world heard of Grave’s story in 1905 when Albert Spalding the founder of Spalding Sports, arranged to assemble a commission that, once and for all, would get to the bottom of baseball’s origins. There was talk that base ball had its roots in England with games like rounders and cricket. Blasphemy, said Spalding. He insisted the game, and the ball that made it possible, was “purely of American origin.” The former National League president Abraham G. Mills headed the commission, and he too believed that the great American pastime had emerged from the US of A, and nowhere else.

Thus, though it was never overtly stated, the commission was pretty intent on combing the nation for iron clad proof of baseball’s All-American roots. Soon they found it when a letter arrived revealing that Graves — now 71-years-old and living 2000 miles away from Cooperstown in Denver, Colorado — wrote an article for the Akron Beacon Journal that described the precise day when Abner Doubleday — all within the space of a few hours — invented baseball by devising its diamond, setting down four bases, a pitcher’s circle and assembling 21 other young men to play ball! (In this game 11 players were on the field).

It’s a nice story, and at the time, everyone believed it. But almost none of it is true.

The Doubleday Baseball was not the first to ever be thrown, hit or caught that June day. Despite Spalding describing the two Abners as “playmates,” Graves was five years old in 1839, Doubleday was 20. Graves said that the players who had assembled the day of the game were from the competing Cooperstown schools of Otsego Academy and Green's Select school, or in another Grave’s article “Green College.” Yet neither of those schools existed. Historian William Ryczek says Graves was an utterly unreliable witness all a round. At one point he claimed to have been a deliveryman for the Pony Express in 1852, except the Pony Express wasn’t founded until 1860. Later in life, Graves shot and killed his wife and was found insane and committed to a psychiatric hospital.

Even more remarkable, Doubleday, the supposed founder of the game, wasn’t in Cooperstown June 12, 1839. He was a cadet at West Point where he would later become a major general in Union Army and play prominent roles during the Civil War at the battles of both Fort Sumter and Gettysburg. He was inventive enough that he patented San Francisco’s famous cable car railway, the one still used today. But he did not invent baseball. In fact, in all of his life-long correspondence, the general never referred to baseball, although during the Civil War he apparently provisioned balls and bats so his troops could play a game now and then. (Troops played the game in both the North and the South.)

Nevertheless, from Spalding’s point of view, and the Mill’s Commissioners’, they had their story and their man. What could be more American than a war hero who, with one simple tale, created the quintessential American game, and the tattered, lemon peel artifact around which it revolved?

Despite all of the fabrications, though, there is something about that ball. I drove to Cooperstown to see it face-to-face. And being a lover of the game, I can tell you I was moved. Not because it was actually the first of its species, but because the ball represented the one thing that has always dominated every aspect of one of the world’s great pastimes.

In truth, baseball, the game, may trace its many roots to Russia (a similar game there was called Lapta), or Germany (Schlagball) or Great Britain (cricket and rounders), or even, as history indicates, on the sandy fields of ancient Egypt.

Wherever its origins, it ultimately made its way to American games like rounders and town ball, where after many additional iterations, we find it in its current form. But the odd ball itself, was created, shaped and marinated in America. It has a history and evolution and life that is so rich and original that it’s almost as if it’s alive. And like other living things it has evolved in ways no less unlikely than the epic journey that has brought so many other creatures from the past to the present; by evolutionary increments, always open to revision.

That matters because at every turn, the nature of the ball, and the unruly ways it developed, fundamentally changed the course of the game’s history from its earliest days. The two can’t be separated, whether it’s from the first balls handmade by the game’s early pitchers to the lightly modified versions in the pre-Covid years that have led to more home runs being hit in all of the game’s history.

If baseball is a game of inches, it’s because of the ball. It’s why the difference between a triple and foul is no more than a “nat’s eyelash.” It why in 1913 “Home Run” Baker hit more homers than anyone else with 12, and in 1927 Babe Ruth hit 60 and then 54 after that and 46 the year after that. It’s why a fast ball traveling at 100 mph can look like a BB coming at a batter when Bob Feller or Randy Johnson threw it, and a beach ball when Pirate Rip Sewell leisurely tossed his looping Eephus ball from the mound. Exact same orb, yet both nearly unhittable. It’s why balls can knuckle, curve, slide and speed in forms and facets that can make grown men cry with frustration. In the long history of the game, if a baseball looked, felt or acted one way, it was a different game from a ball that looked, felt and acted another.

It explains, perhaps by hit or miss, or some mystical fate, why there are four bases, not three, why it takes 90 feet to reach each of them, why a pitched ball does the crazy things it does across a very precise distance of 60 feet and six inches; rather than 59 or 61 feet. Only because of this bald, hard orb, fashioned just so and then lovingly muddied in the secret waters of the Delaware River, could we ever hope to cry out the sanctifying words, “Play ball!” Without it there would be no need for bats or gloves, no World Series, no breathless bottoms of the ninth with two out and a full count, no Jackie Robinson, Roberto Clemente, Hack Wilson, Josh Gibson, “Babe” Ruth, Satchel Paige or Hammerin’ Hank Aaron. There would be no need of curve balls, spitters or fork balls. No screaming line drives, no towering home runs, Baltimore chops, bloops or blasts or squeeze plays. No Ryan Express, Say Hey Kid, Big Poison, Sultan of Swat, Dizzy or Daffy Dean, Catfish Hunter, Bullet Bob Feller, Jughandle Johnny Morrison, Big Poppy or Chicken on the Hill Will. Nor would the Wrigley Fields or Chavez Ravines, Fenway Parks or Camden Yards, nor any of the other fields of dreams scattered around cities, farmlands and sandlots from South Korea and Japan to the Caribbean, and the Americas serve any purpose. And never would we have heard the calls of great announcers, with the words, “And you can kiss it good- bye!”, or “How about that!” or Vin Sculley’s beautiful description of an opening day in Brooklyn: “There’s 29,000 people in the ballpark, and a million butterflies.”

Just as baseball, the game, has woven itself into the fabric of American life, the evolution and life of the ball itself shaped and reshaped its namesake game, and with it, all of the strange characters and incomparable feats that have made the game so memorable.

As spheres go, not many have shaped a nation, nor become the identity of that nation. Somehow this little ball has found ways to transcend politics, bridge generations, soften hardened hearts and bring the high and low together onto common ground, sometimes broken and tearful, sometimes leaping and embracing. Think about it. Over generations there have been few experiences that more deeply bond a child and parent than the simple, repeated act of tossing this particular kind of ball back and forth. Pitcher Jim Bouton might have put it best. “You see, you spend a good piece of your life gripping a baseball; and then in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.”

And so with each iteration, since before the civil war, the “base ball” has driven the evolution of the game and its business and players as together they have fashioned their cocktails of joy and greed, drama and shock. Without that spinning spheroid, this thing that long ago might have begun its life as nothing more than a thrown stick to be stopped before it hit a tombstone; without that, the game could be not called baseball. It would be something else.

But today, as on that mythic day in the summer of 1839, the ball, ever changing and changed, abides. All revolves around it as surely as the sun centers the planets.